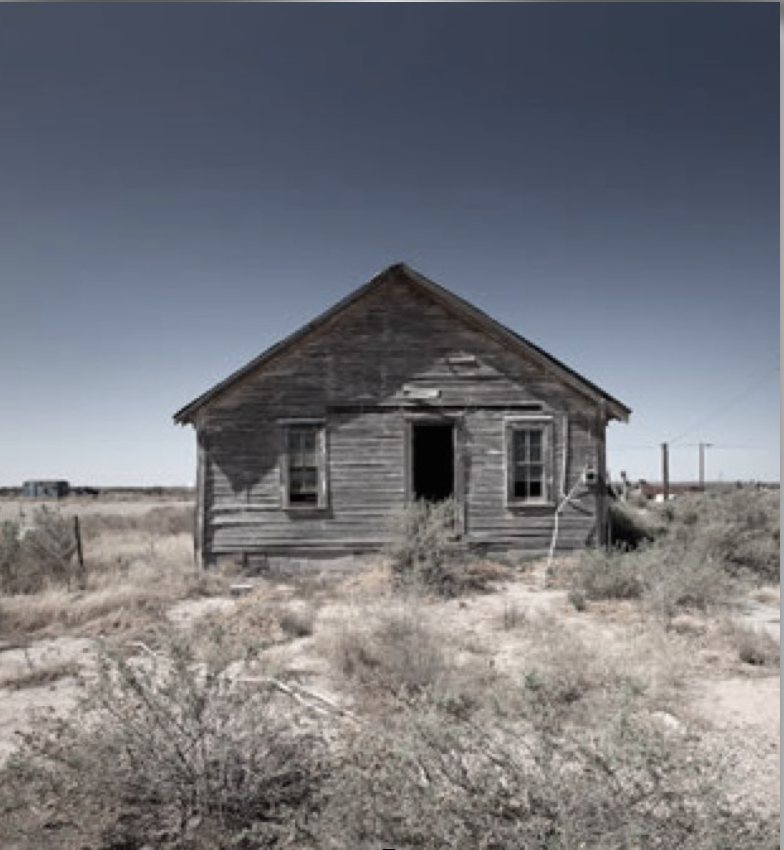

THE BUS RIDE FROM INGLEWOOD ALL THE WAY TO SHERMAN OAKS on that hot July morning was almost unbearable. The streets in 1954 were bumpy, and the buses were stiff, like submarines with wheels, catapulting us into the unconditioned air every time we hit a pothole.

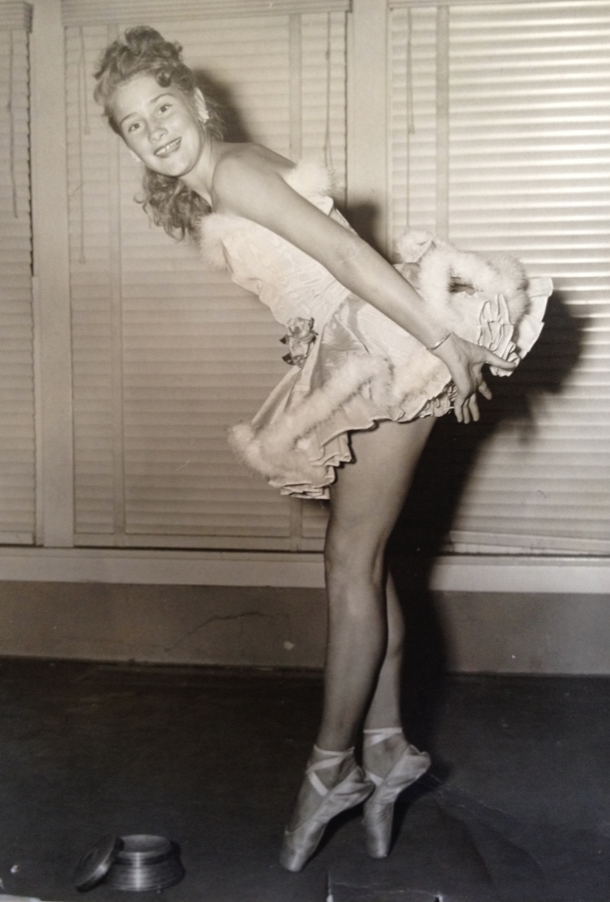

I wouldn’t have been on that stuffy bus if it weren’t for my friend, Margaret Taylor, who was dead set on dancing on television. We had been studying dance together at my Uncle Bob’s studio since we were five years old, and when she found out there was an open audition for dancers on the Horace Heidt television show, she was going to get there come hell or high water. Her parents wouldn’t let her go alone, however, so you guessed it. She made me come along.

Nearly three excruciating hours later, around 10 A.M., we finally passed over the Hollywood Hills and made our way down to the Horace Heidt compound in Sherman Oaks. We found where we were supposed to go and we changed into our leotards in a bathroom. Finally we walked into the studio to find all kinds of gorgeous dancers, all seeming to be about 25 years old, stretching, talking and smoking like crazy. As we walked into the plume of smoke, they looked at us like we were from outer space. We were both 16-year-old, fresh-faced kids standing next to these beautiful women who looked seven feet tall. Margaret was in orange and I was in Easter yellow. We stuck out like sore thumbs. …